Products You May Like

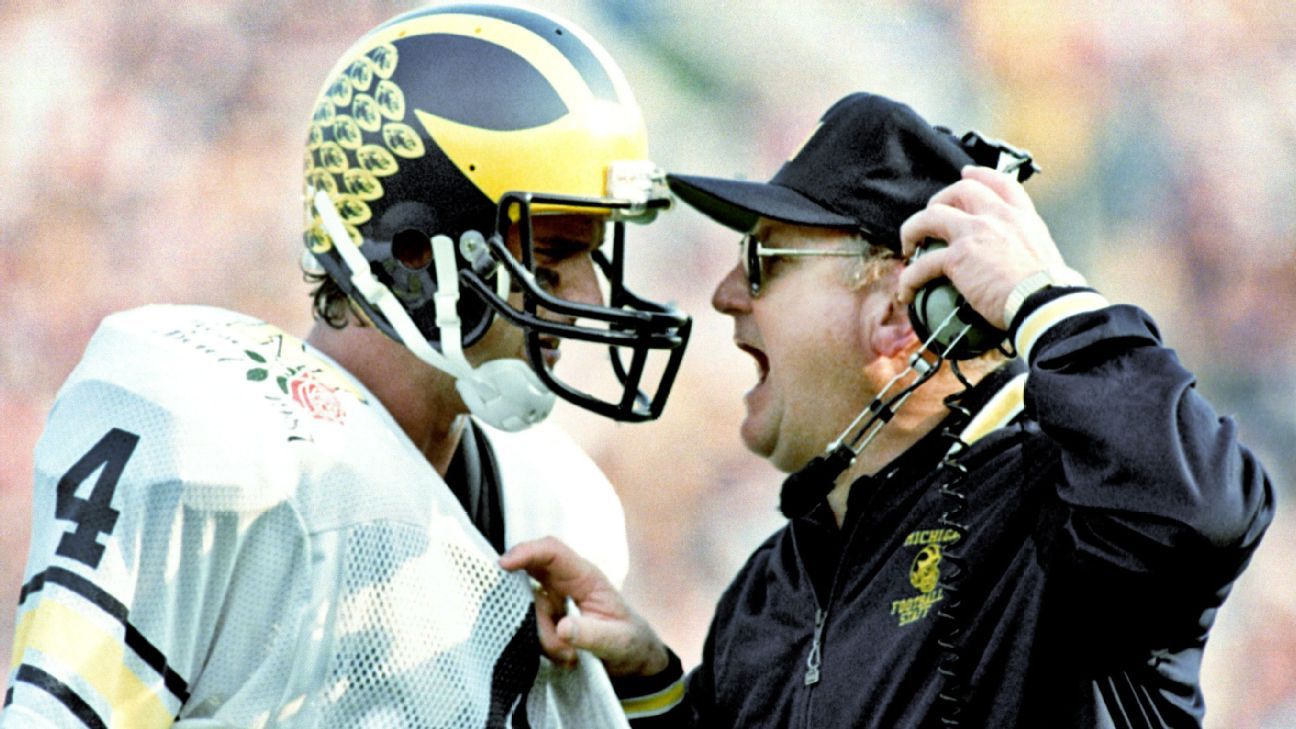

A son of former Michigan football coach Bo Schembechler says he told his father that former team doctor Robert Anderson molested him during a physical exam in the 1960s, and that the revered football coach ignored the complaint and went out of his way to make sure Anderson kept his role with the team.

Matt Schembechler, 62, says he was sexually molested by Anderson when he was 10 years old, within a year of when his adopted father was hired to coach the Wolverines and his family moved to Ann Arbor. Matt says Anderson fondled him and did “an anal probe” when he visited the doctor for a sports physical prior to joining the peewee football team. According to Matt, when he shared those details with Bo, the coach told him he didn’t want to hear about it and then got physically violent with both Matt and his mother.

“That was the first time he closed-fist punched me,” Matt told ESPN. “It knocked me all the way across the kitchen.”

Matt plans to address his claims further in a news conference Thursday afternoon alongside two former Michigan football players who say they also attempted to warn Bo Schembechler about Anderson’s abuse. Anderson and Bo Schembechler both died years before any claims about these issues became public.

Robert Anderson worked at the University of Michigan from 1966 through 2003. During the majority of his time at the school he worked closely with the athletic department, treating athletes’ injuries and conducting annual physicals. Hundreds of former patients — many of them former Wolverine athletes — now say that Anderson sexually abused and harassed them in a variety of ways during the treatment of routine medical issues. In interviews and court documents, Anderson’s former patients say the doctor assaulted them, fondled them and made an array of inappropriate sexual comments, among many other examples of misconduct. Bo died in 2006. Anderson died in 2008.

After a letter from a former university wrestler prompted a 2018 police investigation, the university hired the law firm WilmerHale in 2020 to determine how prior complaints about Anderson were handled. WilmerHale found that multiple employees at the university failed to act when presented with credible complaints that Anderson was sexually abusing his patients.

Matt Schembechler is not the first to allege that Bo knew about Anderson’s abuse. A former student radio announcer said last summer that he told the coach about Anderson in the early 1980s. Several former football players have also told investigators that they spoke to Bo about Anderson’s treatment with varying degrees of specificity when they were playing at Michigan.

Matt told ESPN he had a rocky relationship with Bo throughout their shared lives. Matt sued his father and the University of Michigan in the late 1990s over a dispute about a sports memorabilia company Matt was running. Around that time, he shared some of the details of his upbringing in a GQ magazine article that framed Bo as a bully at home and on the practice field.

Bo Schembechler won 13 Big Ten Championships during his two decades coaching the Wolverines. He also served as the university’s athletic director from 1988 to 1990. He was inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame in 1993, and in 2014 the school commissioned what it calls a “larger-than-life sized” bronze statue of Schembechler, which now sits in front of the football team’s practice facility.

Other former players, including current Michigan head coach Jim Harbaugh, have said that they believe Bo would have taken action if he was presented with evidence that Anderson was molesting his patients.

Bo adopted Matt and two other sons — Chip and Geoffrey — after marrying their mother, Millie, in 1968. Bo and Mille later had one more son named Glenn.

Matt told ESPN that his mother visited Don Canham, then the university’s athletic director, shortly after they told Bo about Anderson’s abuse. Matt, who was still 10 years old at the time, says he remembers his mother saying Canham was prepared to fire Anderson, but Bo intervened.

“Bo went to bat for Anderson and got him back working again,” Matt says. “He wasn’t going to have anybody change his team.”

Anderson continued to treat Michigan’s athletes for more than 30 years. Nearly 900 of his former patients have retained legal counsel and claim they were abused by him. Matt has also hired an attorney and is suing the university.

Millie Schembechler died in 1992. Don Canham died in 2005. No documentation of meetings about Anderson or medical records from Matt’s appointments exist today. Matt says he shared parts of the story with his older brother, Chip, who died in 2003.

Attempts to reach Matt’s two living brothers for comment were unsuccessful. Glenn Schembechler, who goes by Shemy and is Bo’s only biological son, previously told ESPN he was certain no one ever told his father about Anderson’s abuse.

“I can tell you unequivocally no one ever told Bo,” Glenn Schembechler said last summer. “Bo would have done something. … Bo would have fired him.”

Matt said he remembers hearing other athletes talk about Anderson while growing up around the football program, but never shared the details of what happened to him with anyone else because it was embarrassing. He said he didn’t raise the issue with his father again because Bo “made it clear it was not to be talked about.”

Matt says he visited Anderson twice more for sports physicals — once in high school and once before starting his freshman season as a football player at Western Michigan University. Matt said he grabbed Anderson’s wrist when the doctor reached toward his genitals in their next appointment. He said Anderson did not attempt to molest him in the third and final visit.

“I stopped him the second time, and the third time I didn’t let him touch me,” Matt says.

Matt said he is coming forward now to try to let people know that “you can’t abuse people and get away with it no matter how many football games you won.” He said he doesn’t feel strongly about how Schembechler’s coaching legacy should be remembered by the university or its fans.

“He was a great coach and made a lot of people happy. He made a ton of money for the University of Michigan filling that stadium up. He provided, for most of those kids that played for him, a great experience. Maybe it was the greatest experience of their life,” Matt told ESPN. “I think he was a horrible human being.”